No matter who wins the next election, Caesar will remain Caesar, doing some good and some bad. But Christians report to a different king. This issue starts with a provocation. In his opening letter, editor Peter Mommsen suggests Christians are too excited about the wrong politics: “Questions of public justice should matter deeply to Christians. We dare not be indifferent about securing healthcare for all and ending interventionist wars; we must seek to reduce abortions and strengthen families. When an election comes, we should pray and then, perhaps, lend our support to a candidate we judge may, on balance, advance social righteousness. But if the early Christians and the Anabaptists are right, this isn’t the politics that matters most. And so, as a matter of faithfulness, we should question how much it deserves of our passion and time. Our allegiance belongs elsewhere.”In contrast to an election campaign, this politics may feel grittier and less glamorous. This issue of Plough Quarterly explores what this alternate vision of faithful Christian witness in the political sphere might look like. You’ll find articles on:What two leading political theorists of left and right agree onWhat persecution taught Anabaptists about politicsThe Bruderhof’s interactions with the stateTolstoy’s case against making war more humaneHow some Christians read Romans 13 under fascism

No matter who wins the next election, Caesar will remain Caesar, doing some good and some bad. But Christians report to a different king.This issue starts with a provocation. In his opening letter, editor Peter Mommsen suggests Christians are too excited about the wrong politics: “Questions of public justice should matter deeply to Christians. We dare not be indifferent about securing healthcare for all and ending interventionist wars; we must seek to reduce abortions and strengthen families. When an election comes, we should pray and then, perhaps, lend our support to a candidate we judge may, on balance, advance social righteousness. But if the early Christians and the Anabaptists are right, this isn’t the politics that matters most. And so, as a matter of faithfulness, we should question how much it deserves of our passion and time. Our allegiance belongs elsewhere.”

In contrast to an election campaign, this politics may feel grittier and less glamorous. This issue of Plough Quarterly explores what this alternate vision of faithful Christian witness in the political sphere might look like.

You’ll find articles on:- What two leading political theorists of left and right agree on

- What persecution taught Anabaptists about politics

- The Bruderhof’s interactions with the state

- Tolstoy’s case against making war more humane

- How some Christians read Romans 13 under fascism

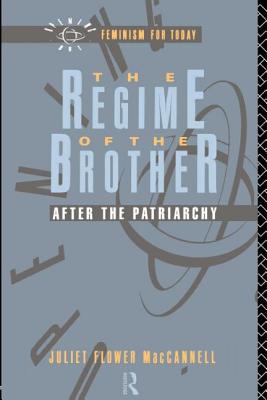

Get Plough Quarterly No. 24 – Faith and Politics by at the best price and quality guranteed only at Werezi Africa largest book ecommerce store. The book was published by Plough Publishing House and it has pages. Enjoy Shopping Best Offers & Deals on books Online from Werezi - Receive at your doorstep - Fast Delivery - Secure mode of Payment

Jacket, Women

Jacket, Women

Woolend Jacket

Woolend Jacket

Western denim

Western denim

Mini Dresss

Mini Dresss

Jacket, Women

Jacket, Women

Woolend Jacket

Woolend Jacket

Western denim

Western denim

Mini Dresss

Mini Dresss

Jacket, Women

Jacket, Women

Woolend Jacket

Woolend Jacket

Western denim

Western denim

Mini Dresss

Mini Dresss

Jacket, Women

Jacket, Women

Woolend Jacket

Woolend Jacket

Western denim

Western denim

Mini Dresss

Mini Dresss

Jacket, Women

Jacket, Women

Woolend Jacket

Woolend Jacket

Western denim

Western denim

Mini Dresss

Mini Dresss